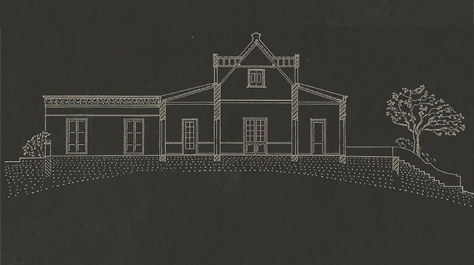

beth haim bleinheim

Virtual tour of selected tombstones

- 01. Hanah Leah, wife of Semuel Hoheb

- 02. The Cohanim and their rituals

- 03. Abraham, son of Daniel Moreno Henriques

- 04. Ishak Senior

- 05. The Spinoza Siblings

- 06. Ieudith Nunes da Fonseca

- 07. Sarah Hana, wife of David Lopes Dias

- 08. Eliaú Rephael Namias de Crasto

-

09. Mordechay Hisquiau Namias de Crasto

and his wife Rachel Hana - 10. Ishac de Marchena

-

11. Abraham, de Jacob Jesurun

and his wife Ester - 12. Mosseh Alvares Correa and his wife Ester

- 13. Jahacob Alvares Correa

- 14. Rachel, wife of Abraham de Chaves

- 15. Mordechay Alvares Correa and his wife Sarah

- 16. Ester, wife of Selomoh Senior

- 17. Ishac Haim Senior and his wife Rachel

- 18. David Senior

-

19. Abigail Aboab Cardozo wife

of Selomoh Nunes Redondo - 20. Ribi Mosseh Haim Alva

- 21. Children’s graves

- 22. Socles without heads

- 23. The Gate of Heaven

- 24. Sarcophagus-shaped tombs

- 25. Monkey puzzle tree

May 19, 1740

Hanah Leah, wife of Semuel Hoheb

Hanah Leah’s tombstone slab demonstrates two of the most frequently found motifs in Beth Haim: a felled tree and a deathbed scene. These two illustrations may be found in countless variations, for an individual variation tells a lot about the deceased. Here Hanah Leah’s tree of life, symbolizing she died in her prime time, is chopped down by an angel. In the case of children sometimes only a branch of the tree of life is chopped off, not the whole trunk as inscribed on Hanah’s tombstone. The deathbed scene tells us in no uncertain terms how Hanah died. She was evidently one of the many young women of bygone years who died in childbirth. In some cases, these deathbed scenes contain references to the biblical account of the death of Rachel, wife of the patriarch Jacob, who died giving birth to their son Benjamin. In these pictures Rachel is seen in a tent beneath a tree because she died while traveling (Genesis 35:17).

July 15, 1727

The Cohanim and their rituals

Often the gravestones of men from the Cohen family may be recognized by the symbol they bear of two hands raised in blessing. In some cases, the hands are surmounted by a priestly crown. In Orthodox tradition, the Cohanim, descendants of Aaron the High Priest, are seen as a priestly caste. On particular festivals they perform certain rites in the temple where they give the priestly blessing in which the tips of the thumbs are placed together and the second and third finger on each hand separated in a V-shape. Before the blessing is given, the Cohanim perform a ritual washing of their hands, carried out by Levites who are members of the tribe of Levy. Some of the slabs in Beth Haim illustrate this ritual washing of the hands, like the tomb of Aaron Levy Maduro (July 15, 1727). This gravestone portrays three Levites, one of which is pouring out water over the hands of a Cohen, while a second stands ready with a towel. A third is holding the basin that catches the water after washing the Cohen’s hands.

March 19, 1726

Abraham, son of Daniel Moreno Henriques

In the world of the Curaçaon Jews, ships played a major role since trade and shipping were the primary sources of the island’s income. Five tombstone slabs in Beth Haim Bleinheim are carved with pictures of ships such as this one from the grave of Abraham Moreno Henriques, who died in 1726. The gravestone of Abraham is made from costly Carrara marble. Such stones were imported via the family in Amsterdam and transported as ballast in the wooden ships sailing to Curaçao. At that time Curaçaon shipping was largely in the hands of the island’s Jewish community. Almost every Jewish merchant owned a ship. However, enormous risks were faced by shipowners, and seafaring was a tough life. Apart from storms and tempests, there was a constant fear of attack from pirates of various nationalities, which frequently operated with the knowledge and blessing of their national governments. An additional hazard for Jews at sea was the threat of capture and the ensuing Spanish Inquisition.

June 25, 1693

Ishak Senior

Many epitaphs from the 17th and 18th century don’t always give the precise age of the deceased but instead suggest an approximate age. On his epitaph, Ishak Senior is described as incurtado, which indicates that he wasn’t yet fifty when he died a victim of an epidemic that raged through the island. In 1685, he arrived in Curaçao together with three brothers. Until his death, Ishak ran a trading enterprise with his brother David. The decorations on Ishak’s marble tombstone all refer to his early death. His tree of life has one branch lopped off and is surrounded by a wood – a possible reference to the strong family ties of the Seniors. At the base of the slab is a richly detailed still life bearing symbols of the transience of life. The bones and garlanded skull are unambiguous. The hourglass refers to the passing of time and with it, life. It bears a feathered wing as well as a bat’s wing, symbols of day (joy) and night (sadness).

January 25, 1695

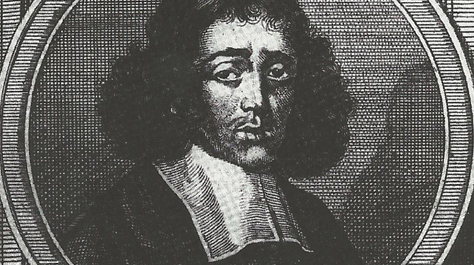

The Spinoza Siblings

Ribca Spinoza’s husband, Semuel de Casseres, died in Amsterdam in 1660. Still a widow, she set off with her children sometime between 1679 and 1685 in search of a better life in Curaçao. She died of yellow fever in 1695, as did her son Michael, who lies buried beside her in Beth Haim Bleinheim. Ribca was the half-sister of the philosopher Baruch Spinoza (1623-1677). Their father, Michael de Espinoza, was a successful businessman and one of the Parnassim of the Amsterdam Jewish community Talmud Torah. His first wife died when Baruch was six years old. Michael died in 1654 and was buried in the Jewish cemetery of Ouderkerk aan de Amstel. Baruch was excommunicated by the Jewish community in 1656 because of some views he held. Although a deeply religious man, he didn’t observe a particular religious belief. Seen as the father of modern philosophy, he was the first secular Jew not attached to any community. Due to his excommunication, he couldn’t be buried in a Jewish cemetery. His grave lies in the cemetery of Nieuwe Kerk in The Hague.

January 18, 1668(?)

Ieudith Nunes da Fonseca

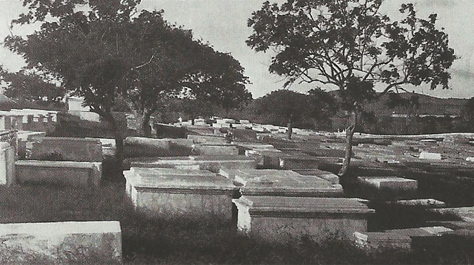

Crumbling stones mark the heart of the most ancient section in Beth Haim Bleinheim. Here, the graves date from the first decades after the founding of the cemetery in 1659. The Jewish settlers couldn’t yet afford to have expensive funerary monuments, so they often built low tombs using coral stone or the local rust-colored basalt. The graves often had a semi-cylindrical form. The settlers would also use terracotta for small tombstones. During renovation work here in 1929, the oldest date-able grave in Bleinheim was uncovered. It belongs to Ieudith Nunes da Fonseca who died probably in 1668 (the final digit of the year of her death isn’t clearly legible). Unfortunately, the precise location of this terracotta tombstone wasn’t documented when it was found, and it was set in a new place, close to the Casa de Rodeos. With the passing years the stone has become completely illegible, but fortunately, it was deciphered during 1936-41. There is also an old photo showing the decoration, with its bouquets of flowers.

February 4, 1716

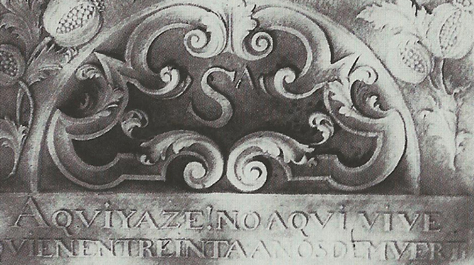

Sarah Hana, wife of David Lopes Dias

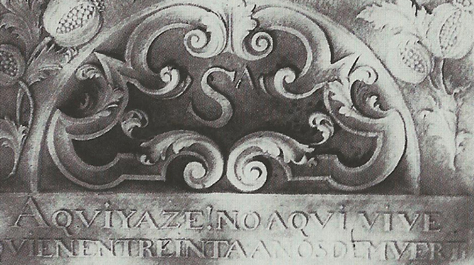

David Lopes Dias lost his wife, Sarah Hana, when she was only 30 years old. He set a marble slab upon her grave bearing an epitaph in Spanish and Hebrew. Its Spanish text is one of the most beautiful in Beth Haim Bleinheim. Today, the still life depicted on Sarah’s tombstone may appear somewhat macabre with its skull, bones and winged hourglass. Sarah’s tombstone is also adorned with an elegant finial. Here the abbreviation sepultura, meaning ‘grave’ is framed with decorative foliage and poppy seed pods, a charming symbol for death representing an eternal sleep. Her husband, David, was one of the most important merchants of his day. The misadventures associated with overseas trading didn’t leave him unscathed. In 1717, two of his ships laden with precious cargoes were captured by Spanish buccaneers. In 1726, David ventured upon the long crossing to Amsterdam which took around three months to sail there. During those long weeks, prayers were recited in the synagogue for his safe passage.

April 2, 1717

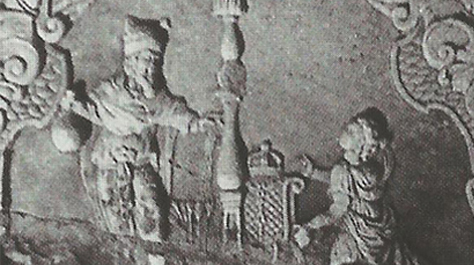

Eliaú Rephael Namias de Crasto

According to tradition and almost without exception, Jewish boys and girls in Curaçao would be given a Hebrew name from the Bible until the mid-twentieth century. Furthermore, grandchildren were named after their grandfather or grandmother. If a child died, the next child born in the family of the same sex would again be given the grandparent’s name with the addition of Haim (meaning ‘life’) – an entreaty to God to grant to the newly born. That the biblical names were considered of great importance can be seen on the gravestones of Beth Haim. They are decorated with many of the transience of life, such as the skull and bones seen here, borrowed directly from Christian pictorial tradition. But the far more frequent and highly detailed biblical scenes illustrating the Hebrew name of the deceased are specifically Jewish. The bas-relief on the grave of Eliaú Rephael Namias de Crasto represents the scene in the Bible where the prophet Elijah takes leave of his successor Elisha, before being carried up into Heaven.

May 5, 1716 and December 25, 1723

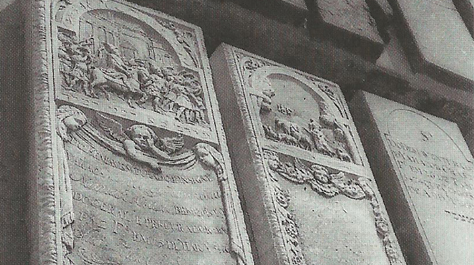

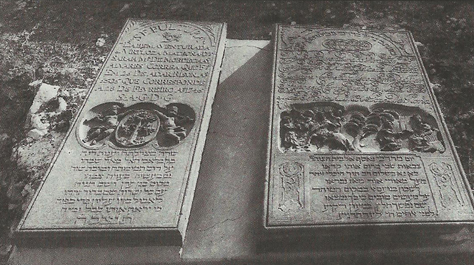

Mordechay Hisquiau Namias de Crasto and his wife Rachel Hana

Whenever possible, couples are buried beside each other, hence married people would reserve adjacent space in the Beth Haim for their burial. In the cemetery of the mother community in Amsterdam, couples sometimes lie together beneath a wide slab, but this is not found in Curaçao. For example, the gravestones of Mordechay and Rachel were given the same decorative design divided into thirds, with the Vanitas at the base telling of the vanity of life and a biblical scene above. These scenes illustrate Mordechay and Rachel’s biblical names. The center field consists of a bas-relief showing sculpted drapery supported by putti, with the epitaph. The following drapery is a sign of social distinction. In his epitaph, Mordechay is referred to as ‘procurer of peace’, because he fulfilled a special role when Curaçao was being besieged by the French (1713) under Admiral J. Cassard. The latter demanded a ridiculously high ransom. Largely thanks to his persuasive words in the governor’s negotiating committee, this was considerably reduced.

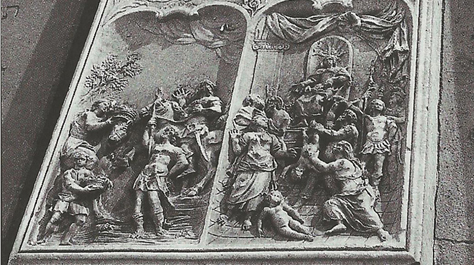

November 16, 1730

Ishac de Marchena

Ishac’s tombstone, like many in Beth Haim Bleinheim, provides a family portrait ingeniously composed with the help of biblical illustrations. Shown here is a beautifully decorated niche in two sections that form a dramatic setting for illustrations of scenes of the biblical Isaac sowing seed (left, Genesis 26:2) and the supplicating Esther (right, Esther 5:7). Ishac’s wife, named Esther, was the daughter of Mordechay de Crasto. At the foot of the stone are two biblical pictures referring to the couple’s sons, Abraham on the left, sacrificing his son (Genesis 22:12) and on the right Mordecai mounted on a horse (Esther 6:9). Ishac held many offices in the Jewish community of Mikvé Israel. When the community decided on building a new synagogue in 1729, Ishac was Second Parnas. The old synagogue had to be torn down to make room for the new building, and Ishac offered his home as a place of worship during the building period. In his epitaph, there is a reference to his hospitable act.

October 6, 1818 and April 20, 1846

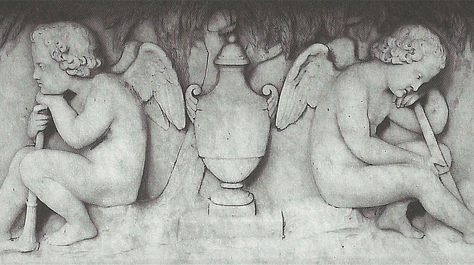

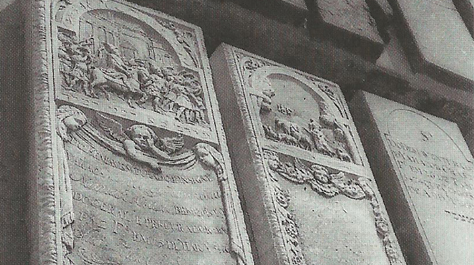

Abraham, de Jacob Jesurun and his wife Ester

This monumental tomb from Italy, is a double grave for the Jesurun couple and was only constructed after the death of Ester, who died almost thirty years after her husband. It is a fine example of the changing fashion in funerary monuments in Curaçao. Following international trends, the Curaçaon Jews also began to construct neo-classical monuments. Decorated on each side with bas-reliefs, this tall tomb derives from Greek and Roman examples. On three sides putti, or cherubs, may be seen grieving, in one instance on either side of a funerary urn, and on one of the other sides beside a veiled urn, symbol of mourning. In a third scene a putto is seen extinguishing a torch which he holds upside-down, snuffing out life. The fourth side of the tomb is the only one to bear a distinctively Jewish symbol, the Star of David. Upon the tomb lies a wide marble slab. On this the epitaphs of the couple are engraved between three columns intertwined with leafy branches.

January 6, 1765 and January 11, 1765

Mosseh Alvares Correa and his wife Ester

In 1734, Mosseh Alvares Correa was the Parnas of Hebrah (the burials and cemetery administrator). He had arranged in 1726 for a rustic wall to be built enclosing Beth Haim at his own expense. Since that date, the wall has always been extended together with the cemetery and tended with care because it’s one of the most valuable historic features of Beth Haim. Mosseh, a merchant and active member of the Jewish community, married his niece Ester, daughter of his sister Gracia and Jahacob Semach Ferro. Ester died just five days after Mosseh and lies buried beside him. Decorating their gravestones is a tree of life in which two doves have settled. In the Talmud, the dove symbolizes the purity, harmony, and chastity of family life. Other graves in Beth Haim where the dove may be seen as a motif referring to the family are those of the Lopes Castro and Halevi families. The epitaph for Mosseh Alvares Correa is as simple and modest as the man himself; it’s a verse from the biblical book of Exodus (19:3).

June 25, 1714

Jahacob Alvares Correa

Engraved on Jahacob’s gravestone is an illustration of the biblical account of Jacob’s Dream: “And he dreamed, and behold a ladder set up on the earth, and the top of it reached to heaven: and behold the angels of God ascending and descending on it” (Genesis 28:12). At the upper end of the slab is the familiar tree of life that has been felled, seen beneath an arch. This semi-circular shape is found on many Jewish gravestones and often forms the only decoration. It is a reference to the stone tablets of the Law, which are often pictured with an arched top. It is a fitting motif for those who chose to have a sober tombstone because of religious conviction, rejecting showiness and splendor. Jahacob’s epitaph is written in Hebrew. As was often the case, it includes citations of biblical texts while the numerical value of the Hebrew letters is used to indicate the year of death. Jahacob, a Torah scholar, was one of the unpaid assistants of Rabbi Eliau Lopez.

September 9, 1705

Rachel, wife of Abraham de Chaves

Again, the picture of a deathbed scene and the felled tree decorate one’s tombstone, this time in costly marble and replete with rich detail. Rachel Alvares Correa, wife of Abraham de Chaves, died in childbirth, and four women are seen bewailing her fate on her tombstone. One of them points significantly towards Heaven. A wet nurse suckles the newborn infant, while the father, Abraham de Chaves, watches in sad confusion. Because the deceased woman was named Rachel, the scene bears resemblances to the story of her biblical namesake’s death: the first Rachel died giving birth to her son Benjamin, while she was traveling (Genesis 35:17). This gravestone may be compared with that of other women who died in childbirth and are buried in the Jewish cemetery of Ouderkerk aan de Amstel near Amsterdam, Holland. Clearly, certain standard illustrations were used and individual variations were made as required.

May 25, 1750 and February 28, 1745

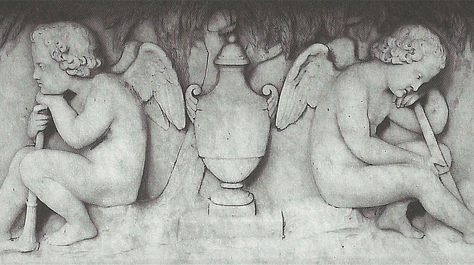

Mordechay Alvares Correa and his wife Sarah

Mordechay Alvares Correa lies buried beside his wife Sarah who died five years before him. He had a bluestone slab carved for her with a medallion in which was a tree of life supported by cherubs. This motif occurs several times in Beth Haim Bleinheim. These chubby, winged boys first appear in Roman mythology. They guarded the human soul upon its journey through life and accompanied it to heaven. They are also linked with Venus and hence are called Cupids. Mordechay used them to express his love for his lost wife. When he died at age 65, he was probably the wealthiest Jew in Curaçao. Around 1748, the Jewish community was temporarily split in two. Mordechay belonged to the party in opposition to the municipal council. In his will he commanded that his body be ritually washed and buried only by his supporters, but his followers were refused the key to access the cemetery and had to force open the gates. The two biblical scenes illustrated refer to his biblical name from the story of Esther.

December 4, 1714

Ester, wife of Selomoh Senior

One of the most remarkable funerary monuments in the Dutch Beth Haim is that of Mosseh de Mordechay Senior who died in 1730. His tombstone bears a design of various portraits, both his own likeness: a picture of Moses carrying the tablets of the Law as well as close relatives. In this sense, the gravestone functions as a family portrait album which depicts his brothers Ishak, Jacob, David and Selomoh, who lived overseas. An Ester and a Rachel feature on his gravestone too, presumably his sisters, though possibly also referring to his Curaçaon sisters-in-law. One of which is Ester (de Marchena y Carilho) Senior. She died many years before her husband Selemoh, whose year of death was 1758. Ester’s symbolic portrait shows the biblical scene in which the young queen Esther reveals her Jewish identity to the king, beseeching him to prevent the wicked plan of Haman to slaughter all Jews (Esther 8:3-4).

April 17, 1726 and July 14, 1746

Ishac Haim Senior and his wife Rachel

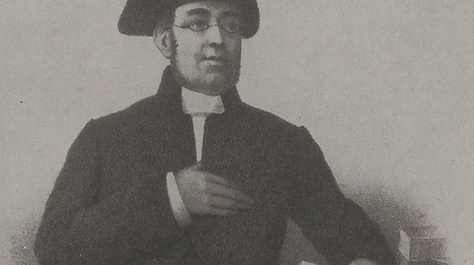

Although the graves of Ishac Haim and his wife Rachel aren’t directly adjacent to each other, the similarity of illustrations on their gravestones makes their connection clear. At the upper center is an arched niche containing the symbolic portraits of Ishac Haim and Rachel, respectively. Left of this is David playing his harp while to the right Abraham is seen peering into the heavens. (Ishac was the son of David Senior, Rachel the daughter of Abraham de Marchena). Interestingly, a biblical figure does not represent Ishac Haim but instead Isaac Aboab da Fonseca, a rabbi and writer from Amsterdam. The picture is a copy of a mezzotint showing the rabbi, drawn from life with his bookshelves in the background by the artist Aernhout Nachtegael and dated 1686. Apparently, this rabbi was so well-known that his portrait served to identify his namesake, Ishac Haim Senior. The portrait of Rachel is a representation in the classical style showing the biblical Rachel as a shepherdess with her flock.

September 13, 1749

David Senior

The Senior family was among the first Jews from the Iberian Peninsula who settled in Amsterdam towards the end of the 16th century. David Senior was one of four brothers who scarcely went to seek their fortunes in the West Indies a hundred years later. Apart from this, David was a prominent figure in the Curaçaon community and supposedly, the governor of the island sought his advice on important matters. David arranged for his gravestone to be made during his lifetime, and he penned his epitaph to beg each reader to pray to God for mercy on his soul. Furthermore, he reserved this place in Beth Haim Bleinheim beside his wife Sara Hana who died in 1730. On the other side lies his grandson, David. To left and right of the sculpted hourglass on his tombstone are two pictures of David: one as a young warrior with the giant Goliath and another as a musician playing upon his harp.

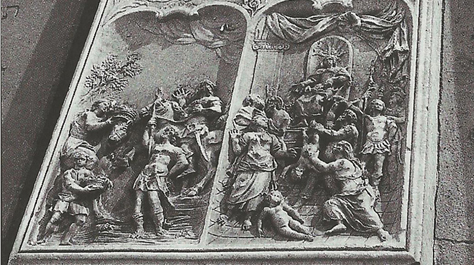

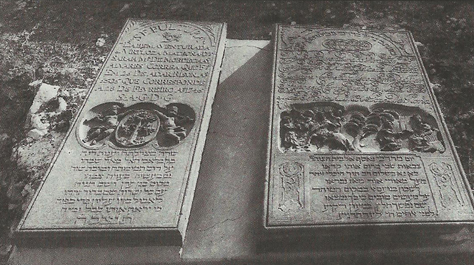

June 18, 1747

Abigail Aboab Cardozo, wife of Selomoh Nunes Redondo

One of the most beautiful tombstones in Beth Haim Bleinheim is that ordered by the sorrowing Selomoh Nunes Redondo as a tribute to his wife Abigail. Unfortunately, we can only appreciate the quality of the sculpture today by studying old photos. On Abigail’s tombstone, Selomoh ordered a diptych to be carved. In the left panel was a scene showing the biblical Abigail offering gifts to king David and in the right, the Judgment of Solomon. This ensured the couple were united even after death. Selomoh was born in Amsterdam in 1700. When his father Mozes de Abraham Nunes died, Selomoh left his wife Deborah with at least five children. She was the sister of Ribi Moshe, first scion of the Maduro family to settle in Curaçao, in about 1672. Ribi Moshe supported his sister and her children financially. Deborah also received financial support for many years from the Amsterdam community. Around 1714, Selomoh and his mother settled in Curaçao.

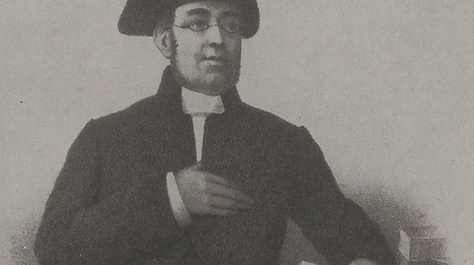

May 19, 1737

Ribi Mosseh Haim Alva

Ribi Mosseh Haim Alva was born in Amsterdam around 1696, and married Ribca Gomes Silva in 1721. Shortly after their wedding, they left for Curaçao where Mosseh became a teacher of the Torah. They had two sons and eight daughters, all born in Curaçao. Mosseh died at the comparatively young age of forty. His tombstone bears a picture of the biblical Moses carrying the Ten Commandments on the stone tablets. The exuberant decoration found on many of the Curaçaon gravestones illustrates that the Jews of the island, like their families back home in Amsterdam, didn’t follow too literally the second commandment which states: “Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image” (Exodus 20:4). However, this in no way implies a lack of religious conviction. The Jews of Spain and Portugal had to hide their religious practices for many years, but at last, in the tolerant atmosphere of Amsterdam and Curaçao, they were able to express their ancient faith.

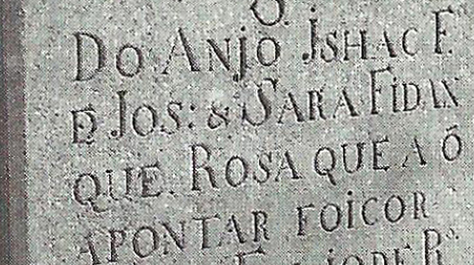

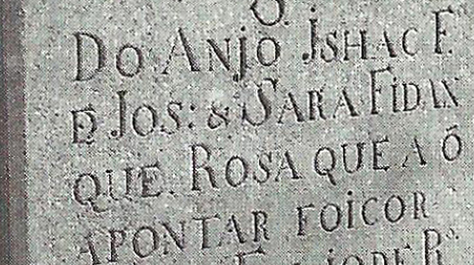

Children’s graves

The many small gravestones in Beth Haim Bleinheim bear witness both to the high rate of infant and child mortality and the deep grief that accompanied the death of a child. These small stones are moving because they suggest a life ended before it had begun. Furthermore, the epitaphs and decorations demonstrate how painful the loss of these young lives was. Children who died before their 13th birthday are referred to on their gravestones as anjo (‘angel’). Of the 2,574 graves in Beth Haim, 545 belong to children. One in three of the Jewish children in Curaçao died young. Incidentally, this figure is relatively low compared to the child mortality rate of 18th-century London. There, two thirds of the children died before they reached the age of five. Close to the graves of Ishac Fidanque and the little David Senior, lies Mordechay Senior. He died in May 1727 at the age of three, shortly after the death of his father Ishac Haim Senior.

Socles without heads

Midway through the 19th century, fashions affecting the design of funerary monuments in Beth Haim Bleinheim changed yet again. Internationally, new neo-classical designs became all the trend. Following the flat stone slabs and the sarcophagus-shaped tombs, there now arose elegant obelisks with carved drapery, enclosed within beautiful cast-iron fence work. In 1852, the young Jacob Pinedo Jr. died in Barranquilla, northwestern Colombia. Three years later Moises de David Jesurun died in New York, also at a very early age. Their families buried them in Curaçao and at their graves, which lay beside each other, placed two marble socles bearing busts of the deceased young men. To the Orthodox rabbi Aron Mendes Chumaceiro (1810-1882), these busts, the lifelike images of the two men, were sacrilegious. Despite Chumaceiro’s opinion, the families refused to remove them. Chumaceiro then asked advice from three rabbis in Amsterdam. When they too condemned them, the young men’s busts were finally taken away.

The Gate of Heaven

Four graves housing members of the Alevy family lie here close together. Each one is designed to resemble a life-size gateway, its pillar twined with leaves and surmounted by an arch. This symbol of a gateway into Heaven through which the righteous shall enter at the end of time is closely interwoven with images referring to the Temple in Jerusalem before its destruction. The Ark holding the Torah scrolls, which stands in every synagogue, will often have a similar appearance. The motif is also frequently met in the designs of title pages of Jewish books and writings. The Jewish Cultural Historical Museum *please link the museum’s website (jewishmuseumcuracao.com) here* (Willemstad) possesses an 18th-century marriage contract with just such a design. The Alevy family graves consist of Ishac Alevy (1764) who is buried beside his first wife, Abigail Hana, who died in 1744, and his second wife Leah, who died in 1774. The fourth grave is that of his son Gabriel Rephael who died in 1770. The ewer and basin pictured here refer to the fact that the family was descended from the tribe of Levi.

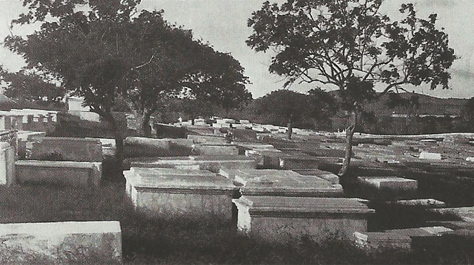

Sarcophagus-shaped tombs

From the close of the 17th century on, the Curaçaon Jews imported their horizontal tombstones of marble or bluestone from Amsterdam. The ornamentation in bas-relief and the epitaphs were carved on the stone in Amsterdam, often by Christian sculptors. Around 1800, the graves were given sarcophagus-shaped tombs, designed according to local building methods, and finished with a layer of plaster. These sarcophagi often also have a marble slab decorated with various motifs and an epitaph. This marble would come from Venezuela and was of far poorer quality than that from Italy. Some of the most beautiful sarcophagi were decorated according to the characteristic Curaçaon architecture. The sarcophagi of Moshe Hisquiao Jesurun (July 17, 1850) and his wife Leah (August 30, 1861) rejoice in rows of stylish small pillars. Equally attractive are the sarcophagi of Benjamin Pereira Brandao (December 13, 1810) and his wife Rachel Calvo (June 20, 1850).

Monkey puzzle tree

In old photos of Beth Haim Bleinheim, there is much more vegetation than nowadays. Sadly, the only remaining tree is the cactus known locally in Papiamento as Kaktus surnam. Wandering through Bleinheim, it becomes evident that trees form an important symbol in the cemetery since the felled tree stands for the life cut down in its prime. The belief in a higher controlling power is demonstrated on tombstones by the hand or the ax appearing from Heaven. Jewish tradition demands that graves be left untouched, so the ground in a cemetery is left to its own devices. However, weeds are now removed from the gravestones in order to protect them. Unlike Christian cemeteries and secular graveyards, there is seldom landscape architecture or planned design for trees, shrubs, and plants in a Jewish cemetery. In 2001, Bleinheim decided to break the rule, but only, in accordance with tradition, outside the eastern wall. A 120-yard-long hedgerow has been planted, consisting of different types of shrubbery such as hibiscus.

May 19, 1740

Hanah Leah, wife of Semuel Hoheb

Hanah Leah’s tombstone slab demonstrates two of the most frequently found motifs in Beth Haim: a felled tree and a deathbed scene. These two illustrations may be found in countless variations, for an individual variation tells a lot about the deceased. Here Hanah Leah’s tree of life, symbolizing she died in her prime time, is chopped down by an angel. In the case of children sometimes only a branch of the tree of life is chopped off, not the whole trunk as inscribed on Hanah’s tombstone. The deathbed scene tells us in no uncertain terms how Hanah died. She was evidently one of the many young women of bygone years who died in childbirth. In some cases, these deathbed scenes contain references to the biblical account of the death of Rachel, wife of the patriarch Jacob, who died giving birth to their son Benjamin. In these pictures Rachel is seen in a tent beneath a tree because she died while traveling (Genesis 35:17).

July 15, 1727

The Cohanim and their rituals

Often the gravestones of men from the Cohen family may be recognized by the symbol they bear of two hands raised in blessing. In some cases, the hands are surmounted by a priestly crown. In Orthodox tradition, the Cohanim, descendants of Aaron the High Priest, are seen as a priestly caste. On particular festivals they perform certain rites in the temple where they give the priestly blessing in which the tips of the thumbs are placed together and the second and third finger on each hand separated in a V-shape. Before the blessing is given, the Cohanim perform a ritual washing of their hands, carried out by Levites who are members of the tribe of Levy. Some of the slabs in Beth Haim illustrate this ritual washing of the hands, like the tomb of Aaron Levy Maduro (July 15, 1727). This gravestone portrays three Levites, one of which is pouring out water over the hands of a Cohen, while a second stands ready with a towel. A third is holding the basin that catches the water after washing the Cohen’s hands.

March 19, 1726

Abraham, son of Daniel Moreno Henriques

In the world of the Curaçaon Jews, ships played a major role since trade and shipping were the primary sources of the island’s income. Five tombstone slabs in Beth Haim Bleinheim are carved with pictures of ships such as this one from the grave of Abraham Moreno Henriques, who died in 1726. The gravestone of Abraham is made from costly Carrara marble. Such stones were imported via the family in Amsterdam and transported as ballast in the wooden ships sailing to Curaçao. At that time Curaçaon shipping was largely in the hands of the island’s Jewish community. Almost every Jewish merchant owned a ship. However, enormous risks were faced by shipowners, and seafaring was a tough life. Apart from storms and tempests, there was a constant fear of attack from pirates of various nationalities, which frequently operated with the knowledge and blessing of their national governments. An additional hazard for Jews at sea was the threat of capture and the ensuing Spanish Inquisition.

June 25, 1693

Ishak Senior

Many epitaphs from the 17th and 18th century don’t always give the precise age of the deceased but instead suggest an approximate age. On his epitaph, Ishak Senior is described as incurtado, which indicates that he wasn’t yet fifty when he died a victim of an epidemic that raged through the island. In 1685, he arrived in Curaçao together with three brothers. Until his death, Ishak ran a trading enterprise with his brother David. The decorations on Ishak’s marble tombstone all refer to his early death. His tree of life has one branch lopped off and is surrounded by a wood – a possible reference to the strong family ties of the Seniors. At the base of the slab is a richly detailed still life bearing symbols of the transience of life. The bones and garlanded skull are unambiguous. The hourglass refers to the passing of time and with it, life. It bears a feathered wing as well as a bat’s wing, symbols of day (joy) and night (sadness).

January 25, 1695

The Spinoza Siblings

Ribca Spinoza’s husband, Semuel de Casseres, died in Amsterdam in 1660. Still a widow, she set off with her children sometime between 1679 and 1685 in search of a better life in Curaçao. She died of yellow fever in 1695, as did her son Michael, who lies buried beside her in Beth Haim Bleinheim. Ribca was the half-sister of the philosopher Baruch Spinoza (1623-1677). Their father, Michael de Espinoza, was a successful businessman and one of the Parnassim of the Amsterdam Jewish community Talmud Torah. His first wife died when Baruch was six years old. Michael died in 1654 and was buried in the Jewish cemetery of Ouderkerk aan de Amstel. Baruch was excommunicated by the Jewish community in 1656 because of some views he held. Although a deeply religious man, he didn’t observe a particular religious belief. Seen as the father of modern philosophy, he was the first secular Jew not attached to any community. Due to his excommunication, he couldn’t be buried in a Jewish cemetery. His grave lies in the cemetery of Nieuwe Kerk in The Hague.

January 18, 1668(?)

Ieudith Nunes da Fonseca

Crumbling stones mark the heart of the most ancient section in Beth Haim Bleinheim. Here, the graves date from the first decades after the founding of the cemetery in 1659. The Jewish settlers couldn’t yet afford to have expensive funerary monuments, so they often built low tombs using coral stone or the local rust-colored basalt. The graves often had a semi-cylindrical form. The settlers would also use terracotta for small tombstones. During renovation work here in 1929, the oldest date-able grave in Bleinheim was uncovered. It belongs to Ieudith Nunes da Fonseca who died probably in 1668 (the final digit of the year of her death isn’t clearly legible). Unfortunately, the precise location of this terracotta tombstone wasn’t documented when it was found, and it was set in a new place, close to the Casa de Rodeos. With the passing years the stone has become completely illegible, but fortunately, it was deciphered during 1936-41. There is also an old photo showing the decoration, with its bouquets of flowers.

February 4, 1716

Sarah Hana, wife of David Lopes Dias

David Lopes Dias lost his wife, Sarah Hana, when she was only 30 years old. He set a marble slab upon her grave bearing an epitaph in Spanish and Hebrew. Its Spanish text is one of the most beautiful in Beth Haim Bleinheim. Today, the still life depicted on Sarah’s tombstone may appear somewhat macabre with its skull, bones and winged hourglass. Sarah’s tombstone is also adorned with an elegant finial. Here the abbreviation sepultura, meaning ‘grave’ is framed with decorative foliage and poppy seed pods, a charming symbol for death representing an eternal sleep. Her husband, David, was one of the most important merchants of his day. The misadventures associated with overseas trading didn’t leave him unscathed. In 1717, two of his ships laden with precious cargoes were captured by Spanish buccaneers. In 1726, David ventured upon the long crossing to Amsterdam which took around three months to sail there. During those long weeks, prayers were recited in the synagogue for his safe passage.

April 2, 1717

Eliaú Rephael Namias de Crasto

According to tradition and almost without exception, Jewish boys and girls in Curaçao would be given a Hebrew name from the Bible until the mid-twentieth century. Furthermore, grandchildren were named after their grandfather or grandmother. If a child died, the next child born in the family of the same sex would again be given the grandparent’s name with the addition of Haim (meaning ‘life’) – an entreaty to God to grant to the newly born. That the biblical names were considered of great importance can be seen on the gravestones of Beth Haim. They are decorated with many of the transience of life, such as the skull and bones seen here, borrowed directly from Christian pictorial tradition. But the far more frequent and highly detailed biblical scenes illustrating the Hebrew name of the deceased are specifically Jewish. The bas-relief on the grave of Eliaú Rephael Namias de Crasto represents the scene in the Bible where the prophet Elijah takes leave of his successor Elisha, before being carried up into Heaven.

and his wife Rachel Hana

May 5, 1716 and December 25, 1723

Mordechay Hisquiau Namias de Crasto and his wife Rachel Hana

Whenever possible, couples are buried beside each other, hence married people would reserve adjacent space in the Beth Haim for their burial. In the cemetery of the mother community in Amsterdam, couples sometimes lie together beneath a wide slab, but this is not found in Curaçao. For example, the gravestones of Mordechay and Rachel were given the same decorative design divided into thirds, with the Vanitas at the base telling of the vanity of life and a biblical scene above. These scenes illustrate Mordechay and Rachel’s biblical names. The center field consists of a bas-relief showing sculpted drapery supported by putti, with the epitaph. The following drapery is a sign of social distinction. In his epitaph, Mordechay is referred to as ‘procurer of peace’, because he fulfilled a special role when Curaçao was being besieged by the French (1713) under Admiral J. Cassard. The latter demanded a ridiculously high ransom. Largely thanks to his persuasive words in the governor’s negotiating committee, this was considerably reduced.

November 16, 1730

Ishac de Marchena

Ishac’s tombstone, like many in Beth Haim Bleinheim, provides a family portrait ingeniously composed with the help of biblical illustrations. Shown here is a beautifully decorated niche in two sections that form a dramatic setting for illustrations of scenes of the biblical Isaac sowing seed (left, Genesis 26:2) and the supplicating Esther (right, Esther 5:7). Ishac’s wife, named Esther, was the daughter of Mordechay de Crasto. At the foot of the stone are two biblical pictures referring to the couple’s sons, Abraham on the left, sacrificing his son (Genesis 22:12) and on the right Mordecai mounted on a horse (Esther 6:9). Ishac held many offices in the Jewish community of Mikvé Israel. When the community decided on building a new synagogue in 1729, Ishac was Second Parnas. The old synagogue had to be torn down to make room for the new building, and Ishac offered his home as a place of worship during the building period. In his epitaph, there is a reference to his hospitable act.

and his wife Ester

October 6, 1818 and April 20, 1846

Abraham, de Jacob Jesurun and his wife Ester

This monumental tomb from Italy, is a double grave for the Jesurun couple and was only constructed after the death of Ester, who died almost thirty years after her husband. It is a fine example of the changing fashion in funerary monuments in Curaçao. Following international trends, the Curaçaon Jews also began to construct neo-classical monuments. Decorated on each side with bas-reliefs, this tall tomb derives from Greek and Roman examples. On three sides putti, or cherubs, may be seen grieving, in one instance on either side of a funerary urn, and on one of the other sides beside a veiled urn, symbol of mourning. In a third scene a putto is seen extinguishing a torch which he holds upside-down, snuffing out life. The fourth side of the tomb is the only one to bear a distinctively Jewish symbol, the Star of David. Upon the tomb lies a wide marble slab. On this the epitaphs of the couple are engraved between three columns intertwined with leafy branches.

January 6, 1765 and January 11, 1765

Mosseh Alvares Correa and his wife Ester

In 1734, Mosseh Alvares Correa was the Parnas of Hebrah (the burials and cemetery administrator). He had arranged in 1726 for a rustic wall to be built enclosing Beth Haim at his own expense. Since that date, the wall has always been extended together with the cemetery and tended with care because it’s one of the most valuable historic features of Beth Haim. Mosseh, a merchant and active member of the Jewish community, married his niece Ester, daughter of his sister Gracia and Jahacob Semach Ferro. Ester died just five days after Mosseh and lies buried beside him. Decorating their gravestones is a tree of life in which two doves have settled. In the Talmud, the dove symbolizes the purity, harmony, and chastity of family life. Other graves in Beth Haim where the dove may be seen as a motif referring to the family are those of the Lopes Castro and Halevi families. The epitaph for Mosseh Alvares Correa is as simple and modest as the man himself; it’s a verse from the biblical book of Exodus (19:3).

June 25, 1714

Jahacob Alvares Correa

Engraved on Jahacob’s gravestone is an illustration of the biblical account of Jacob’s Dream: “And he dreamed, and behold a ladder set up on the earth, and the top of it reached to heaven: and behold the angels of God ascending and descending on it” (Genesis 28:12). At the upper end of the slab is the familiar tree of life that has been felled, seen beneath an arch. This semi-circular shape is found on many Jewish gravestones and often forms the only decoration. It is a reference to the stone tablets of the Law, which are often pictured with an arched top. It is a fitting motif for those who chose to have a sober tombstone because of religious conviction, rejecting showiness and splendor. Jahacob’s epitaph is written in Hebrew. As was often the case, it includes citations of biblical texts while the numerical value of the Hebrew letters is used to indicate the year of death. Jahacob, a Torah scholar, was one of the unpaid assistants of Rabbi Eliau Lopez.

September 9, 1705

Rachel, wife of Abraham de Chaves

Again, the picture of a deathbed scene and the felled tree decorate one’s tombstone, this time in costly marble and replete with rich detail. Rachel Alvares Correa, wife of Abraham de Chaves, died in childbirth, and four women are seen bewailing her fate on her tombstone. One of them points significantly towards Heaven. A wet nurse suckles the newborn infant, while the father, Abraham de Chaves, watches in sad confusion. Because the deceased woman was named Rachel, the scene bears resemblances to the story of her biblical namesake’s death: the first Rachel died giving birth to her son Benjamin, while she was traveling (Genesis 35:17). This gravestone may be compared with that of other women who died in childbirth and are buried in the Jewish cemetery of Ouderkerk aan de Amstel near Amsterdam, Holland. Clearly, certain standard illustrations were used and individual variations were made as required.

May 25, 1750 and February 28, 1745

Mordechay Alvares Correa and his wife Sarah

Mordechay Alvares Correa lies buried beside his wife Sarah who died five years before him. He had a bluestone slab carved for her with a medallion in which was a tree of life supported by cherubs. This motif occurs several times in Beth Haim Bleinheim. These chubby, winged boys first appear in Roman mythology. They guarded the human soul upon its journey through life and accompanied it to heaven. They are also linked with Venus and hence are called Cupids. Mordechay used them to express his love for his lost wife. When he died at age 65, he was probably the wealthiest Jew in Curaçao. Around 1748, the Jewish community was temporarily split in two. Mordechay belonged to the party in opposition to the municipal council. In his will he commanded that his body be ritually washed and buried only by his supporters, but his followers were refused the key to access the cemetery and had to force open the gates. The two biblical scenes illustrated refer to his biblical name from the story of Esther.

December 4, 1714

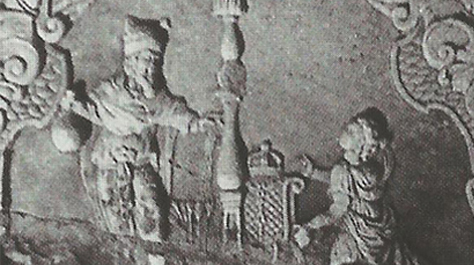

Ester, wife of Selomoh Senior

One of the most remarkable funerary monuments in the Dutch Beth Haim is that of Mosseh de Mordechay Senior who died in 1730. His tombstone bears a design of various portraits, both his own likeness: a picture of Moses carrying the tablets of the Law as well as close relatives. In this sense, the gravestone functions as a family portrait album which depicts his brothers Ishak, Jacob, David and Selomoh, who lived overseas. An Ester and a Rachel feature on his gravestone too, presumably his sisters, though possibly also referring to his Curaçaon sisters-in-law. One of which is Ester (de Marchena y Carilho) Senior. She died many years before her husband Selemoh, whose year of death was 1758. Ester’s symbolic portrait shows the biblical scene in which the young queen Esther reveals her Jewish identity to the king, beseeching him to prevent the wicked plan of Haman to slaughter all Jews (Esther 8:3-4).

April 17, 1726 and July 14, 1746

Ishac Haim Senior and his wife Rachel

Although the graves of Ishac Haim and his wife Rachel aren’t directly adjacent to each other, the similarity of illustrations on their gravestones makes their connection clear. At the upper center is an arched niche containing the symbolic portraits of Ishac Haim and Rachel, respectively. Left of this is David playing his harp while to the right Abraham is seen peering into the heavens. (Ishac was the son of David Senior, Rachel the daughter of Abraham de Marchena). Interestingly, a biblical figure does not represent Ishac Haim but instead Isaac Aboab da Fonseca, a rabbi and writer from Amsterdam. The picture is a copy of a mezzotint showing the rabbi, drawn from life with his bookshelves in the background by the artist Aernhout Nachtegael and dated 1686. Apparently, this rabbi was so well-known that his portrait served to identify his namesake, Ishac Haim Senior. The portrait of Rachel is a representation in the classical style showing the biblical Rachel as a shepherdess with her flock.

September 13, 1749

David Senior

The Senior family was among the first Jews from the Iberian Peninsula who settled in Amsterdam towards the end of the 16th century. David Senior was one of four brothers who scarcely went to seek their fortunes in the West Indies a hundred years later. Apart from this, David was a prominent figure in the Curaçaon community and supposedly, the governor of the island sought his advice on important matters. David arranged for his gravestone to be made during his lifetime, and he penned his epitaph to beg each reader to pray to God for mercy on his soul. Furthermore, he reserved this place in Beth Haim Bleinheim beside his wife Sara Hana who died in 1730. On the other side lies his grandson, David. To left and right of the sculpted hourglass on his tombstone are two pictures of David: one as a young warrior with the giant Goliath and another as a musician playing upon his harp.

of Selomoh Nunes Redondo

June 18, 1747

Abigail Aboab Cardozo, wife of Selomoh Nunes Redondo

One of the most beautiful tombstones in Beth Haim Bleinheim is that ordered by the sorrowing Selomoh Nunes Redondo as a tribute to his wife Abigail. Unfortunately, we can only appreciate the quality of the sculpture today by studying old photos. On Abigail’s tombstone, Selomoh ordered a diptych to be carved. In the left panel was a scene showing the biblical Abigail offering gifts to king David and in the right, the Judgment of Solomon. This ensured the couple were united even after death. Selomoh was born in Amsterdam in 1700. When his father Mozes de Abraham Nunes died, Selomoh left his wife Deborah with at least five children. She was the sister of Ribi Moshe, first scion of the Maduro family to settle in Curaçao, in about 1672. Ribi Moshe supported his sister and her children financially. Deborah also received financial support for many years from the Amsterdam community. Around 1714, Selomoh and his mother settled in Curaçao.

May 19, 1737

Ribi Mosseh Haim Alva

Ribi Mosseh Haim Alva was born in Amsterdam around 1696, and married Ribca Gomes Silva in 1721. Shortly after their wedding, they left for Curaçao where Mosseh became a teacher of the Torah. They had two sons and eight daughters, all born in Curaçao. Mosseh died at the comparatively young age of forty. His tombstone bears a picture of the biblical Moses carrying the Ten Commandments on the stone tablets. The exuberant decoration found on many of the Curaçaon gravestones illustrates that the Jews of the island, like their families back home in Amsterdam, didn’t follow too literally the second commandment which states: “Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image” (Exodus 20:4). However, this in no way implies a lack of religious conviction. The Jews of Spain and Portugal had to hide their religious practices for many years, but at last, in the tolerant atmosphere of Amsterdam and Curaçao, they were able to express their ancient faith.

Children’s graves

The many small gravestones in Beth Haim Bleinheim bear witness both to the high rate of infant and child mortality and the deep grief that accompanied the death of a child. These small stones are moving because they suggest a life ended before it had begun. Furthermore, the epitaphs and decorations demonstrate how painful the loss of these young lives was. Children who died before their 13th birthday are referred to on their gravestones as anjo (‘angel’). Of the 2,574 graves in Beth Haim, 545 belong to children. One in three of the Jewish children in Curaçao died young. Incidentally, this figure is relatively low compared to the child mortality rate of 18th-century London. There, two thirds of the children died before they reached the age of five. Close to the graves of Ishac Fidanque and the little David Senior, lies Mordechay Senior. He died in May 1727 at the age of three, shortly after the death of his father Ishac Haim Senior.

Socles without heads

Midway through the 19th century, fashions affecting the design of funerary monuments in Beth Haim Bleinheim changed yet again. Internationally, new neo-classical designs became all the trend. Following the flat stone slabs and the sarcophagus-shaped tombs, there now arose elegant obelisks with carved drapery, enclosed within beautiful cast-iron fence work. In 1852, the young Jacob Pinedo Jr. died in Barranquilla, northwestern Colombia. Three years later Moises de David Jesurun died in New York, also at a very early age. Their families buried them in Curaçao and at their graves, which lay beside each other, placed two marble socles bearing busts of the deceased young men. To the Orthodox rabbi Aron Mendes Chumaceiro (1810-1882), these busts, the lifelike images of the two men, were sacrilegious. Despite Chumaceiro’s opinion, the families refused to remove them. Chumaceiro then asked advice from three rabbis in Amsterdam. When they too condemned them, the young men’s busts were finally taken away.

The Gate of Heaven

Four graves housing members of the Alevy family lie here close together. Each one is designed to resemble a life-size gateway, its pillar twined with leaves and surmounted by an arch. This symbol of a gateway into Heaven through which the righteous shall enter at the end of time is closely interwoven with images referring to the Temple in Jerusalem before its destruction. The Ark holding the Torah scrolls, which stands in every synagogue, will often have a similar appearance. The motif is also frequently met in the designs of title pages of Jewish books and writings. The Jewish Cultural Historical Museum *please link the museum’s website (jewishmuseumcuracao.com) here* (Willemstad) possesses an 18th-century marriage contract with just such a design. The Alevy family graves consist of Ishac Alevy (1764) who is buried beside his first wife, Abigail Hana, who died in 1744, and his second wife Leah, who died in 1774. The fourth grave is that of his son Gabriel Rephael who died in 1770. The ewer and basin pictured here refer to the fact that the family was descended from the tribe of Levi.

Sarcophagus-shaped tombs

From the close of the 17th century on, the Curaçaon Jews imported their horizontal tombstones of marble or bluestone from Amsterdam. The ornamentation in bas-relief and the epitaphs were carved on the stone in Amsterdam, often by Christian sculptors. Around 1800, the graves were given sarcophagus-shaped tombs, designed according to local building methods, and finished with a layer of plaster. These sarcophagi often also have a marble slab decorated with various motifs and an epitaph. This marble would come from Venezuela and was of far poorer quality than that from Italy. Some of the most beautiful sarcophagi were decorated according to the characteristic Curaçaon architecture. The sarcophagi of Moshe Hisquiao Jesurun (July 17, 1850) and his wife Leah (August 30, 1861) rejoice in rows of stylish small pillars. Equally attractive are the sarcophagi of Benjamin Pereira Brandao (December 13, 1810) and his wife Rachel Calvo (June 20, 1850).

Monkey puzzle tree

In old photos of Beth Haim Bleinheim, there is much more vegetation than nowadays. Sadly, the only remaining tree is the cactus known locally in Papiamento as Kaktus surnam. Wandering through Bleinheim, it becomes evident that trees form an important symbol in the cemetery since the felled tree stands for the life cut down in its prime. The belief in a higher controlling power is demonstrated on tombstones by the hand or the ax appearing from Heaven. Jewish tradition demands that graves be left untouched, so the ground in a cemetery is left to its own devices. However, weeds are now removed from the gravestones in order to protect them. Unlike Christian cemeteries and secular graveyards, there is seldom landscape architecture or planned design for trees, shrubs, and plants in a Jewish cemetery. In 2001, Bleinheim decided to break the rule, but only, in accordance with tradition, outside the eastern wall. A 120-yard-long hedgerow has been planted, consisting of different types of shrubbery such as hibiscus.