The graves at Beth Haim Bleinheim and at Beth Haim Berg Altena have in common that all burials – as is the case at all Jewish cemeteries - are underground.

Burial

Traditions

The graves at Beth Haim Bleinheim and at Beth Haim Berg Altena have in common that all burials – as is the case at all Jewish cemeteries – are underground. Once the casket (or in the past a corpse wrapped in a burial shroud) has been lowered, the grave is hermetically closed with earth and (in modern times) cement. The marble tombs and sometimes quite elaborately decorated sepulchral monuments are not more than empty sarcophagi!

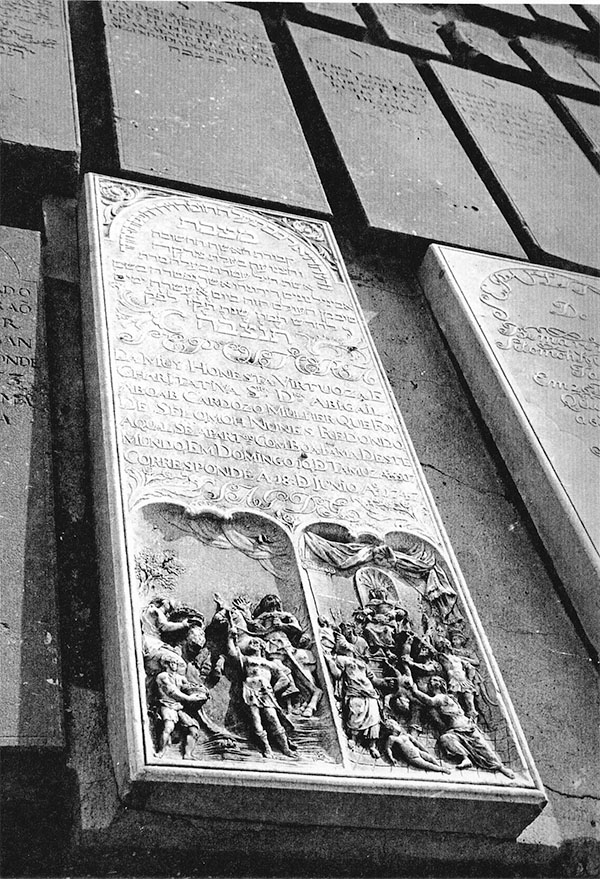

The first graves in Beth Haim Bleinheim were made of local coral stone or basalt and shaped in a semi-cylindrical form. Occasionally, a grave was made of terracotta until the prosperity of the local Jewish community led to an increase of imported marble and bluestone slabs carved into tombstones. Many of the graves at Bleinheim were engraved with beautiful imagery displaying biblical motifs and epitaphs in various languages. The tombs at Beth Haim Berg Altena are – with a few exceptions – rectilinear and generally showing only the name, dates of birth and death, sometimes the place of birth and/or death, and sometimes limited symbolism or text.

While the settlers in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries lived mostly in the area close to the Bleinheim cemetery, that changed as Curaçao’s Jews got deeply involved in commercial trading and moved to live in the city of Willemstad. Now burials at Bleinheim became cumbersome as they required transporting the deceased and family and friends by barge to the Blenheim plantation and then climbing up by a public road to arrive at the cemetery for the interment. And any family member living in or around the city wanting to visit the grave of a loved one at Beth Haim Bleinheim would also have had quite a ways to go to do so.

Burials at Berg Altena, which is within walking distance of Jews living in or near the city, was much less cumbersome. Berg Altena was the site of two adjoining cemeteries – a Reform cemetery starting in 1863 and an Orthodox cemetery as of 1880, each with its own rituals and customs. Initially the Orthodox ritual at Berg Altena did not differ much from that utilized at Bleinheim, but the liberal Reform ritual from the start was much less ceremonial. That is also the case today with burials consisting mostly of a selection of prayers, a eulogy and the opportunity for all present to deposit three scoops of loose dirt on the casket as a symbolic way of assisting in the actual burial.

tombstone Beth Haim bleinheim 1950’s

Two cemeteries (ad)join at berg Altena

Donate to help

Casa de Rodeos

at bleinheim

at Berg Altena

In Orthodox Jewish Sephardic tradition, it is customary for the grieving to walk seven times in procession around the body of a deceased adult male prior to burial in a building known as the Casa de Rodeos. This building obtains its name from the Portuguese word for this procession, rodeamentos (hakkafot in Hebrew). There are Casas de Rodeos at both Beth Haim Bleinheim and on the western section of Beth Haim Berg Altena, the section where Orthodox members of the Mikvé Israel community were buried. Liberal burial customs do not include a procession around the body and therefore there is no Casa de Rodeos on the eastern, original Reform section of Beth Haim Berg Altena. Atop the entrances to the Casas de Rodeos at both cemeteries there is an inscription which reads, “They that are born are destined to die and the dead to be brought to life again” (Ethics of the Fathers, Pirke Avot, 4:29).

Cazinha dos Cohanim

According to Orthodox Jewish tradition, descendants of Aaron are forbidden from walking on the hallowed ground of cemeteries. These descendants are known as the Cohanim (or Cohens) and are traditionally of a priestly caste. To allow the Cohanim in Curaçao to witness the burials of family members without having to walk near the graves, the Cazinha dos Cohanim (House of the Cohens) was established at Beth Haim Bleinheim. This building allowed the Cohanim to witness burials that were across the cemetery. There is no similar structure at Beth Haim Berg Altena.

The hands with spread fingers, as shown above, symbolize descendants of the Cohen family

FAQ

Most frequent questions and answers

Beth Haim means “House of Life” and added to the specific location it is used to denote Sephardic cemeteries. In the Pirke Avot or Ethics of the Fathers it is written: “They that are born are destined to die and the dead will be brought to life again.”

Beth Haim Bleinhem is thought to have been founded in 1659 while various additional plots were added to it between 1759 and 1822. It was originally located on plantation ‘Blij en Heijm’ or ‘Blynheim’ which was acquired by the predecessor of Shell Curaçao after the establishment of the refinery to the east of the cemetery.

The oldest tomb in Beth Haim Bleinheim was likely in 1668. The oldest discovered Jewish tombs in the Americas are not at Beth Haim Bleinheim but in Barbados and likely in Recife which for part of the 17th century was owned by the Dutch. Beth Haim Bleinheim is the oldest walled-in cemetery in the Americas and continued in use into the 1960’s.

Chemical emissions of the adjoining oil refinery and wind erosion have led to the complete deterioration of the historic sepulchral art and inscriptions of virtually all of the tombs. Numerous unsuccessful efforts have been undertaken to try to protect the gravestones form the refinery’s harmful emissions and to rescue the beautiful historic sepulchral art and inscriptions.

Starting in 1864, eastern part of the Berg Altena cemetery was used for burial of members of the new Reform Community Temple Emanu-El, its first burial being the interment of Dr. Salomon de Leon in 1865. In 1880 the western part of the cemetery became a more conveniently located burial site for members of Mikvé Israel as transporting the deceased by barge to Bleinheim or visiting graves there became increasingly cumbersome. The first burial by Sephardic Mikvé Israel at their new Berg Altena cemetery was an Ashkenazi Jew, David Meijer, in 1880.

The Orthodox Sephardic tradition required walking seven times in procession around the body of a deceased adult male prior to interment. In Portuguese these circuits are called rodeamentos and took place in each of the two Casas de Rodeo. The two story building at Beinheim is the Cazinha dos Cohanim and enabled the descendants of the priestly tribe to observe burials without having to enter the cemetery.

In 1943 2570 graves were identified at Bleinheim but it is estimated that there might well be another 2500 graves which have totally deteriorated or of which the deceased was buried only in a shroud. There are app. 1270 tombs at Beth Haim Berg Altena.

Of the tombs at Bleinheim 73% have Portuguese and 16% Spanish inscriptions. At Berg Altena there is not even one tomb with a Portuguese inscription, 56% have Spanish and 21% have English inscriptions.